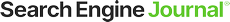

There are many words which are spelled the same but have different meanings based on language and location. A very simple example is the word “football”. In the US and Canada refers to a game played with a ball that is thrown in the air and carried towards a goal; while, in the UK and Australia it refers to a game that is played by kicking a ball into a goal (also known as ‘soccer’ to Americans). So, how does Google determine which meaning of a specific word a user is after?

Query Challenge

Every time someone conducts one of these ambiguous searches on Google, Google’s algorithm immediately needs to figure out the preferred language of the user to just understand the category of results that should be returned before even determining the rankings of those results.

While the word football is spelled the same by all English speakers, a human audience would not know which type of game is being referenced in a conversation unless they knew where the person talking about the game came from. In both games, there are similar features like a great deal of running, passing, and even goal kicking.

Screenshot of Google.com vs Google.com.mx. 5-30-14

Screenshot of Google.com vs Google.com.mx. 5-30-14Spoken Advantages

Within a very short spoken conversation or statement there would probably not even be any semantic clues that could help the listener figure out which kind of football was being referenced. If someone just asked, “What time is the football game?” or “Do you play football?”, the answer would be dependent on the specific kind of football. (When listening to ambiguous phrases, there may be the prevalence of an accent, but this advantage will not exist for typed phrases in a search box.) However, if the conversation is expanded the listener will eventually be able to figure out whether the primary topic is American football or soccer.

Similar to spoken conversation, in longer queries, Google will also use adjoining words to the ambiguous term to help refine the query. A query like “football pitch” would mean that a user is looking for soccer, and “football field goal” would mean that it is an American (or Canadian) football query. Furthermore, Google uses additional query words combined with timing to understand the query. “What time is the football game?” searched on an NFL game day Sunday would be a great indicator of the query intent of the user.

One Word Query

When the query is just one word, this becomes far more challenging. Figuring out which kind of sport a user is seeking is certainly a challenge, but at least both variations are referring to a game. Google could just return results for both definitions of football, but that would not be a very good user experience. An American seeking the NFL would not understand why there are results for soccer in the search page.

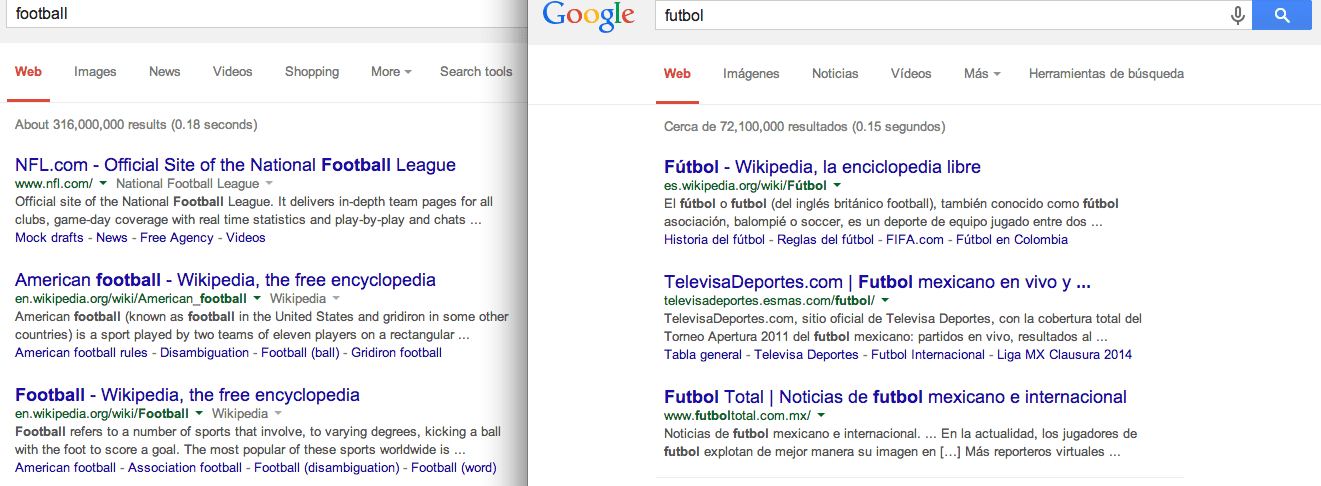

Google is able to get away with returning different categories of results in ambiguous queries like “breadcrumbs” because a user understands that Breadcrumbs could have multiple meanings. In the screenshot below, Google is returning results for recipes, the breadcrumb design element, a product, and a book. All of these make sense, and there is no sense that Google failed to interpret the query. Adding a result from another culture or language is a lot more jarring.

Google search for Breadcrumbs Screenshot 5-30

Google search for Breadcrumbs Screenshot 5-30This is an even greater challenge for the dozens of examples where a word means one thing in a language, but has a different meaning entirely in another language. In English, a “gift” is something nice you give to people, while in German, a gift is poison. In France, “pain” is bread, while in English, it is something we try very hard to avoid. (For some off-color examples, have a look at this Reddit thread.)

Language Prioritization for User Experience

If Google were to return results across multiple languages, the user would probably think there was something wrong with Google and use another search engine. It is even more important in these cases that Google correctly determines the user’s preferred language and returns only relevant results.

If there are other words that accompany the multi-use word, Google can use these to match the user’s language and return the best result. As before, the real challenge is when there is only a one-word query.

To try to parse the user’s language, Google is going to heavily rely on all of the user’s past history with search and most of the time this will be all they need. A user that usually searches in English will most likely want an English result. A query for “football” that comes fairly close to a query for “Steelers” would be a strong indication that the user is not interested in soccer results. Going even deeper into the full user history a user that clicked on World Cup results in the past would probably be interested in Soccer results. For those that are fans of conspiracy theories, Google could potentially use data like previous history of watching sports videos on YouTube or time spent on sports site with Doubleclick retargeting pixels to give them a more complete picture of the user. (See Google’s ad preferences [Canadian link] for what they know about your individual activities)

Five Levers to Determine Language Preferences

Nonetheless, even with all the data they have gathered on users there will be many instances where past history will not help. For these instances, Google looks at five different areas to help them determine how they interpret the query. (An Adwords support page claims to only use user settings at least for Adwords, but other language ads will more than likely accompany whatever language they determine to be the query.)

User Account Preferences

If the user has an account with Google, at the time they setup the account they were either forced to choose a language and location in the sign-up process or they were defaulted into one. If a user’s settings declare their preferences to be English, and US, Google will first assume that the likely language of any query will be American English. These preferences also populate the default search preferences, which can be found under search settings on a Google search page.

If a Google account user decided they wanted to start seeing results in another language or locale they would need to manually change their language preferences. These can be changed just for search under the search settings options or for all Google products under the account settings. Changing language and location preferences will impact anywhere a user conducts logged in searches including other computers and mobile devices.

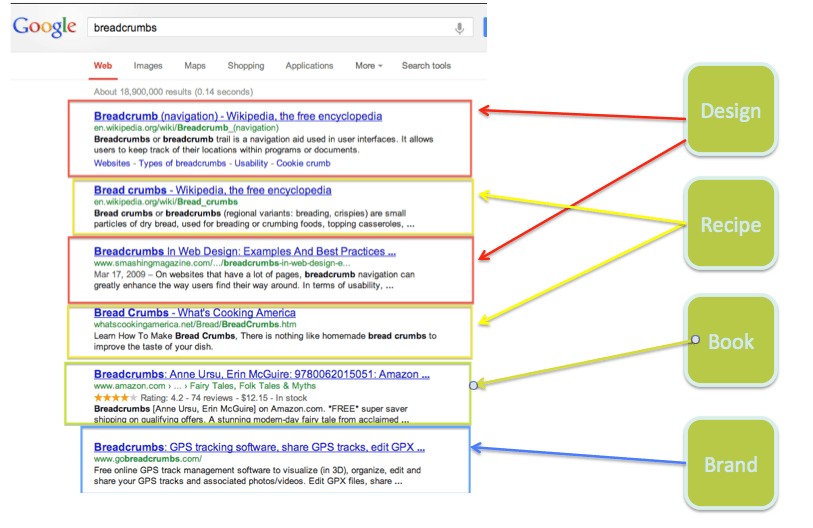

Browser Settings

Since not all Internet users have Google accounts or always logged-in, if they are Google account holders, Google’s first backup for account level language settings is a similar setting at the browser level. In all modern browsers, there is a default setting which declares a user’s language preferences. Google will use a browser’s location and location preference as the primary clue for a user’s language intent.

In most cases, the language setting is defaulted to how the user installed the browser. If the browser was downloaded in English from a US mirror, it will probably be set to English and US.

For Chrome and Firefox, these settings can be adjusted at the browser level, however, to change settings for IE and Safari, this actually needs to be done at the system level – a pretty big change to just do some Google testing.

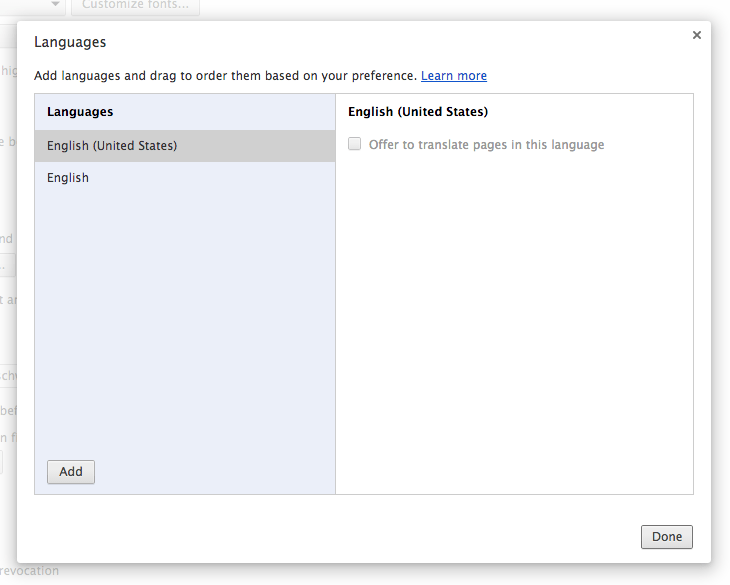

Chrome language preferences Screenshot on 5-30-14

Chrome language preferences Screenshot on 5-30-14Geolocation

Often times, just relying on either Google account or browser settings doesn’t give Google’s algorithm complete confidence in the desired language of a query. To add a higher degree of certainty, they will see where the user is physically located.

Generally, Google relies on physical locations of a user a great deal in order to better target search results. A user in the US that searches for “Giants” on the East Coast of the United States will see more New York Giants results on the first Google results – even during the NFL off-season, while a West Coast user will see more San Francisco Giants results – even during the MLB off-season.

For many queries, there won’t be a great degree of difference in the search results conducted on Google.com from various locations, but there will be some queries that see some major shifts. For example, a query for the word “football” will be nearly identical in the US, Canada, and the UK; while, a query for the word “holiday” will be very different in the UK than it is from the US.

TLD of Google Domain

While physical location is an important clue for a user’s language intent, it will very rarely override any of the account or browser level language settings. However, the Google TLD (e.g. Google.com vs Google.co.uk) where the query was conducted can override these settings.

Google.com.br screenshot 5-30

Google.com.br screenshot 5-30Typically, a logged-in user will default to Google.com even if they are traveling outside the US. A non-logged-in user will get redirected to whatever the local Google TLD is even if their browser settings indicate that they prefer English and US.

TLD is a very important factor in determining in what language to return results, and if there was a hierarchy in Google’s language determination processing, it could either be first or simply go hand-in-hand with location targeting. The TLD can one of the best clues Google has for language intent if the user intentionally chose to the specific TLD.

For example, a user in the US who conducted a search on Google.com.br very likely would like to see Portuguese results. On the other hand, it can be a poor clue if the user was simply directed to that TLD by their location as a traveler might have been. In the traveler example, an US resident traveling in Germany that conducted a Google search while logged-out from their account would see Google.de by default simply because of their location. Google relying on the TLD as a determinant of their language intent might end up giving the user poor results.

If this user searched the word “handy” they would see results related to mobile phones because this is what Germans use to refer to a cell phone. The user might very well have been interested in the types of results that Google would have shown in the US, but did not get to see them because of an incorrect language choice.

When Google uses TLD for language assumptions, they always default to the primary language of a country. In Canada where both English and French are official languages, a query for the word “baguette” would return English results even though it is technically a French word. The same defaults would be occur in Switzerland where even though German, French, and Italian are widely spoken, Google always assumes that a query is in German whenever there is any doubt.

Query Parsing and Matching

Lastly, Google tries to break down the word itself looking for any clues as to the language. The algorithm matches the word itself against word matches in the most common languages. Once a language is matched via a keyword, all results will most likely be in that specific language. This is fairly simple when the word is spelled correctly and only matches a single popular language. It is a bit more complicated when it is not a perfect match.

In these cases, Google will look for things like statistical matches towards a misspelling in a specific language versus another. The word “football” can be spelled “futbal” “futbol” and “futball”, so Google will try to guess using all the rest of the rest clues to determine if the user made a spelling mistake or whether results in another language were actually sought. For any technically minded readers, more details about this process can be gleaned from Google’s patent on the topic.

TLDR

SEO’s typically focus on the aspects of Google’s algorithm that decide in what position a webpage should be ranked. In reality, Google’s algorithm is far more complex than an ordering of content based on scores. They actually need to conduct a real-time analysis on every query to determine the user’s language before they can even start retrieving sites from the index and determining the ranking for each of these pages.

I hope this brief look into how Google determines a queries language gave you some interesting food for thought on how hard Google works to satisfy a user and provide a high level of quality in their results. I have not found any Google source which shares how they determine ranking, and the findings above came from my own research. If you have discovered or just know something different, I would love to hear more about it.

Featured image via Flickr